My “parade car” is a 1974 Plymouth Valiant. I enjoy driving it, now and then, and it still runs beautifully. It has plenty of torque, so there aren’t any issues with lack of power around town, though highway ramps require a little planning.

Built in Newark, in a plant which has been replaced by a University of Delaware campus, the car originally cost $4,252 — ($2,906 for the base four-door sedan, $646 for the automatic transmission and a bunch of décor items, $395 for air conditioning, various other options, and destination charge). In those days, though, the minimum wage was $2 an hour, and you were supposed to be able to live off it. Today’s equivalent from the government’s CPI calculator is $21,655.

Today’s equivalent, since there are no more Dodge Darts, could be a 2018 Chevrolet Cruze LS with the six-speed automatic — boasting twice the number of forward gears as my old Valiant (with its three-speed).

Do the two cars compare? Isn’t the Valiant known for durability? The footprint is much larger, so is it fair to look at today’s Cruze?

Let’s start with durability. The Valiant’s powertrain would go on “forever,” which in those days meant 200,000+ miles, but the rest of the car wasn’t quite so long-lasting. The Cruze was built to a “200,000 miles without major failures” goal; the Valiant, to a 100,000 mile goal.

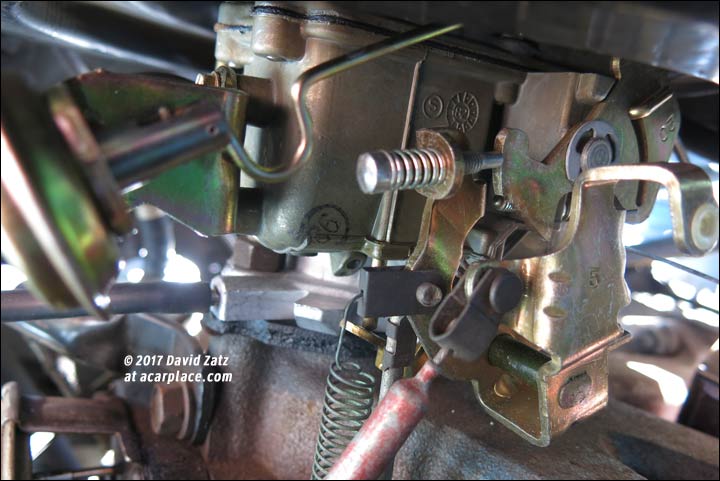

New cars don’t have carburetors, distributors, points, or rotors.

The two cars also occupy about the same marketing/product-line space. The legroom is similar, with an edge to the Cruze; the Valiant is a bit wider. Trunk space is similar; the Cruze’s is deeper and more practical, while the Valiant’s has a gas pipe crossing over and numerous exposed wires.

The Valiant has some advantages over the Cruze. The added width and bench seats (“sofa seats” if you must) let you carry six people, as long as the middle passengers had very short legs; there were six seat belts (four of them were just lap belts). The older car had rear wheel drive, optional vinyl covered roofs, and optional fender-mounted blinkers. It was also relatively free of distractions.

There, the advantages end.

The Cruze is far safer in any test than the Valiant; it weighs about the same amount, but the engine generates a good deal more horsepower and has a six speed automatic which also helps. Modern cars have far better sound insulation, including thicker acoustic windows, which is one reason they weigh as much as the older cars even though they use lighter materials (better steel alloys, more aluminum, much more plastic). They also have much better radios, with six speakers, bigger woofers, and standard FM stereo along with USB input — which would have been hard in 1974, given the lack of a USB standard or, for that matter, affordable portable storage devices that could hold enough data for music.

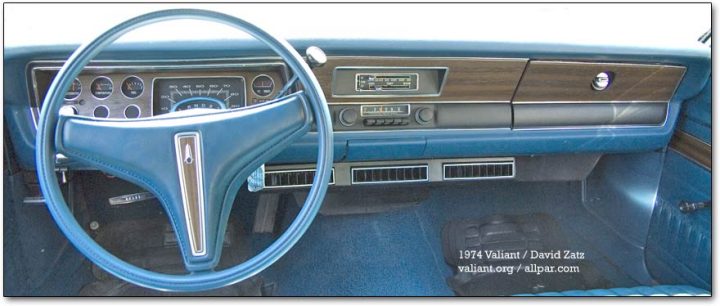

As for the saying that today’s cars have too much plastic, we’ll let you decide… that’s not real wood, you know (admittedly it’s bolted or glued to a steel frame). The climate control is arguably more driver-friendly in the Valiant, but the fan has only three speeds, and there aren’t that many choices.

Let’s look at the instrumentation, too. The Valiant has a nice, sensible 100 mph speedometer (earlier cars went to 120, newer ones to 85). The Chevy provides all the same gauges but the ammeter, though you can show a voltmeter in the center. Chevy’s inane 160 mph speedometer is too tight and could 50-mph markings and such, but you do get a tachometer, and it’s much more clear at night. The standard compass is nice, too.

Those bench seats could be comfortable, but today’s buckets replaced them for a good reason, and it wasn’t just imitating whatever the Japanese did. They’re safer and more comfortable. We all get shoulder belts (with pre-tensioning for added safety), the shoulder belts are more comfortable and easier to use, and they work with six or more airbags. Perhaps older cars could survive a crash better than new ones, but humans in new cars survive crashes better than they did in old cars… the car sacrifices itself to save the human, and that’s a good thing. We won’t even bring in new side impact and rollover protections.

Modern cars are quiet inside, as quiet as high-end luxury cars were in the 1960s and 1970s. Normal 1970s cars didn’t have acoustic glass, or nearly as much sound insulation, and aerodynamics took a distant back seat to styling. Second-gen Valiants are not quiet inside.

As to maintenance and repairs, it’s often said that older cars were often easier to repair; they had to be, because they needed more repairs and maintenance. Tuneups twice a year (plugs, points, rotor, timing), regular greasing of suspension fittings, oil changes every 3,000 to 6,000 miles, tires wearing out every other year, alternator or ball joint replacements every few years, annual radiator fill and flush — these have all been consigned to history. Now plugs last 80,000 miles, antifreeze is the same; oil changes can be as long as a year apart with the engine computer reminding you when to do them; and parts like alternators don’t fail until the car is quite old. In my experience, parts tend to come off newer cars without nearly as much effort, and many things are actually easier to change out.

Moving to the outside, I don’t think there’s a single passenger car today that can’t beat the Valiant, easily, in a road race — that is, they all handle better, take turns faster, and stop faster, and most accelerate more quickly, too. It’s hard to find a car with lower 0-60 times than a 1970s straight-six. That’s not to diss the straight sixes, either; many of today’s base-model four-cylinders can easily outrace the standard V8 sedans and coupes of years passed. Yes, the 3.7-liter slant six was all you needed in the city, and you can pass 85 on the highway without too much fuss, but it wasn’t as quick to accelerate as the 1.4-turbo in the Chevy.

Dare we bring up gas mileage? In theory, the Valiant could hit the high twenties, maybe even thirty in pure highway with careful driving. In reality, they tended to bring back the teens in city driving and roughly 20-22 on the highway (going up to 65 only). Those three-speeds’ optimal gas-mileage speed was likely around 35-40, given the horrific aerodynamics. We reached 27 city, 34 highway, in our Cruze; the EPA rating is 30/40.

Overall, there’s no question but that current cars in the “reasonable price range” are a far better deal than, at least, the mid-1970s, pre-fuel-crisis cars were. You get much more in the way of safety, performance (any kind of performance), and creature comforts, with sound systems only the craziest audiophile could dream of in 1974 — and even they probably wouldn’t believe you could fit hundreds of albums onto a portable disk that fit in your center console.

Just as the Valiant was an incredibly good deal compared with a 1930 Chevrolet, the Cruze (or just about any car in its class) is an incredibly good deal compared with the 1970s compacts. Time moves on, and we make progress in materials, engineering, computerization, and packaging; and the same money ends up buying more. It’s good, sometimes, to be reminded of that.

Admittedly, in some cases we lost things we may like or love as time goes on. Many older cars had grand styling, beautiful lines, or impractical touches. Some simply felt better when you drove them. We may have grown seriously attached to some aspect of driving our car, whether it be a 1940 Packard or a 1974 Valiant. But let’s not forget why people buy these things in the first place… and, when some guy comes up to you at a car show and starts talking about how the old cars were so much better … ask him why he didn’t drive one into the show.

David Zatz has been writing about cars and trucks since the early 1990s, including books on the Dodge Viper, classic Jeeps, and Chrysler minivans. He also writes on organizational development and business at toolpack.com and covers Mac statistics software at macstats.org. David has been quoted by the New York Times, the Daily Telegraph, the Detroit News, and USA Today.

Leave a Reply